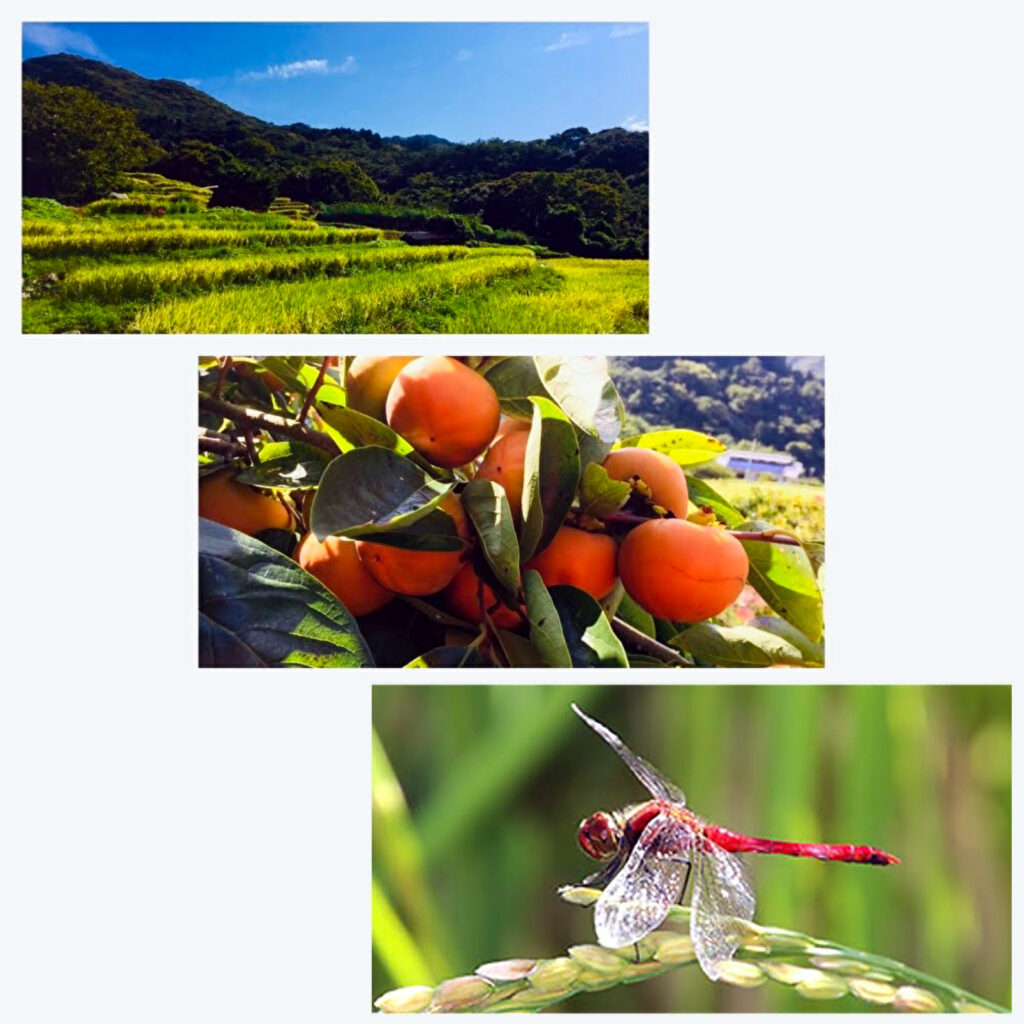

From Demachiyanagi Station in Kyoto’s Sanjo area, trains head to “Yase-Hieizanguchi Station” and “Kurama Station.” The first line to open was the one to Yase-Hieizanguchi Station, known as the Eizan Main Line. Later, the Kurama Line was created by branching off from the Eizan Main Line at Takaragaike to reach Kurama Station. Together, these are called Eizan Electric Railway (commonly referred to as Eizan Railway). Spring offers cherry blossoms, summer showcases lush greenery, autumn boasts vibrant foliage, and winter reveals snowy landscapes—this is a place where Japan’s four seasons can be thoroughly enjoyed. Especially in this season, both the Eizan Main Line and the Kurama Line offer spectacular views of autumn leaves.

Today, I visited Rurikoin Temple, a hidden gem for autumn foliage enthusiasts. Situated at the foot of Mount Hiei and at the entrance of Yase, a valley along the Koya River with views of the Wakatan mountain range to the west, this temple belongs to the Jodo Shinshu sect. The name “Ruri” (lapis lazuli) refers to one of the seven treasures that adorn the Pure Land of Paradise and represents the sacred blue of the Pure Land. The main garden, covered in layers of moss and surrounded by dense maple trees with a pure spring bubbling up, radiates a brilliance resembling the hue of lapis lazuli, which is how the temple got its name, “Rurikoin.”

Rurikoin is a branch of Muryojuzan Komyoji Temple in Gifu Prefecture and was originally designed as a villa. It began as a retreat for Gentarou Tanaka, the founder of Kyoto Electric Light (the predecessor of Eizan Electric Railway), and was initially named “Kikakutei” by Sanjo Sanetomi. During the Taisho and Showa periods, the current buildings and gardens were developed on its 12,000-tsubo (approximately 40,000-square-meter) grounds. The shoin (study hall), built in the refined sukiya style, was designed by the renowned Kyoto sukiya architect Sotoji Nakamura.

One of the most popular spots within Rurikoin is the second floor of the shoin, where the Ruri Garden reflects on the desks and floors. The natural light gently filters into the room, and the sight of the autumn leaves mirrored on the lacquered desks—the so-called “upside-down maples”—creates a fantastical beauty, as if one is being drawn into a world inside a mirror.

京都三条の出町柳駅からは「八瀬比叡山口駅」行きと「鞍馬駅」行きが出ています。最初に開通したのが「八瀬比叡山口駅」行きで、この線を叡山本線と言います。後に叡山本線の「宝ヶ池」から分岐して「鞍馬駅」行きの鞍馬線ができます。併せて叡山電鉄(通称叡山電車)と呼びます。春は桜、夏は緑樹、秋は紅葉、冬は雪景色と、日本の四季をここだけで満喫できる風景が広がっています。中でも今の季節、叡山本線に乗っても鞍馬線に乗っても最高の紅葉が楽しめます。

今日訪ねた瑠璃光院は知る人ぞ知る紅葉の隠れ名所です。比叡山の麓に位置し、西に若丹山地を望む高野川沿いの渓谷に位置する八瀬の入り口にある浄土真宗の寺院です。瑠璃とは、極楽浄土を飾る七宝の一つである浄土の色。種々の楓が繁茂する深山の地に、幾重もの苔に覆われ清らかな泉が湧く、その主庭全体がまさに瑠璃色に輝かんとする様子から「瑠璃光院」という寺号がつけられました。

瑠璃光院は、岐阜県にある浄土真宗 無量寿山光明寺の支院で、もともとは別荘として設計されました。叡山電鉄の前身である「京都電燈」の創業者、田中源太郎の庵として始まり、三条実美によって当初「喜鶴亭」と名付けられました。1万2000坪の敷地に大正から昭和にかけて現在の建物と庭園が整備され、数寄屋造りの書院は京数寄屋造りの名人と称される中村外二によって造営されました。

瑠璃光院の中でも最も人気のスポットである書院2階からは、瑠璃の庭が書院の机や床にリフレクションする様子が一望できます。自然光が室内に柔らかく差し込み、秋の紅葉が漆塗りの机に映し出される逆さ紅葉は、まるで鏡の中に吸い込まれてしまうような幻想的な美しさです。